There is no electricity, no concrete, no corrugated sheet, no plastic waste, but sacred stones, millet and the controversial practice of pruning girls and boys. Visit to the Dogon country in Mali.

The tour guide has drops of sweat on his forehead – and not only because of the heat. An unsuspecting tourist just shook one of the loosely stacked sandstones in the surrounding wall with his backpack.

‘For God’s sake. Be careful! If that stone had fallen, we would have argued for hours. That would have been a terrible violation of taboos.’ Behind the wall lives a hogon from the village of Djigibombbo, a kind of high priest. And the Dogons in Mali, West Africa, believe that the stone that falls from this wall would bring misfortune to the whole village.

Even before visiting the first Dogon village, Said El Idrissi el Bechkaoui, a guide to the study tour from Munich, swore the group on the rules: never get off track. Always follow a local village guide in a column one after another, who always leads the way. Never sit on stones without question, even if it seems temptingly located next to the hut.

Demons lurk everywhere

A visit to remote and inaccessible Dogon villages in southeastern Mali, not far from the border with Burkina Faso, is complicated: demons lurk everywhere, and on almost every corner, without suspecting a European, he could stand with his foot and Break one of many taboos. Some roads and places are forbidden to women, others to men.

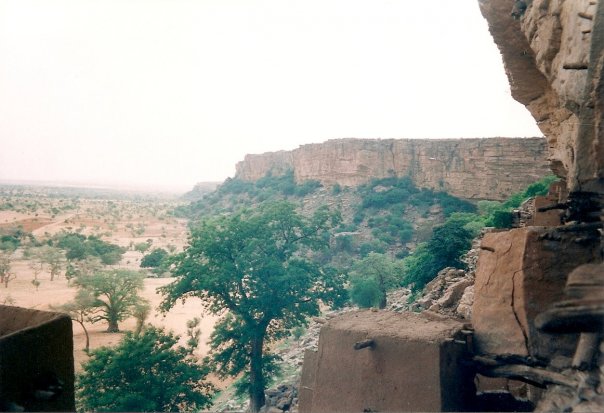

The Dogons live in several hundred small villages on the cliff of Bandiagar, a 300-meter-high cliff that opens south to the Gondo plain. To this day, many villages stick to yellow-red sandstone cliffs like bizarre nests. The more you get away from the capital Sanga, which can be reached by road from Moptia, the more authentic everyday life is.

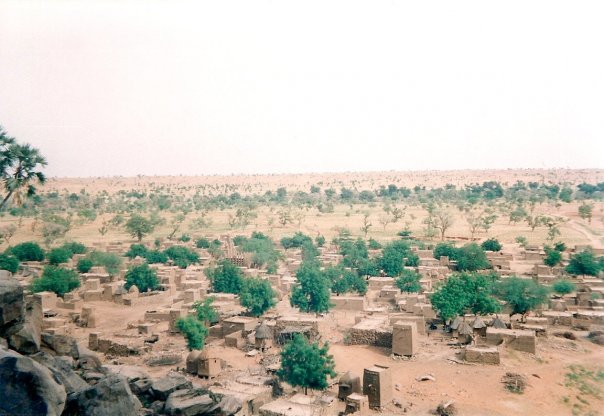

In Nongon, which can be reached after a two-hour drive off the road from Bandiagara through the bushes, there is no electricity, no concrete, no corrugated sheet or plastic waste. The nearest market is a three-hour walk. The entire village is built of sandstone and clay, and millet granaries wear straw hats. A group of children chasing and singing a welcome song, just like that. Women beat millet under baobabs, men irrigate lush green onion fields on the edge of the village.

Animistic and patriarchal traditions

The Dogons have preserved their animistic and patriarchal traditions to this day, although Islam has now taken over most of the village. ‘More than 50 percent of the Dogon are Muslims, but at the same time, 100 percent are also animists,’ says Said El Idrissi, an Islamic scholar and tour guide. Many Dogons have managed to avoid Islam so far. Ancestor worship, religious cults and belief in cosmic forces dominate their lives.

According to their belief, Amma, the only God, created heaven and earth, sun, moon, stars and several smaller gods. He used red copper for the sun and warmed it, while for the moon he used white copper. He created one human being in a bright light, which made it black, and another on a muffled moonlight, which is why ‘white look pale like nymphs’. One of the most important cults is the Dance of Masks, which is celebrated as a funeral ceremony and usually lasts for several days. For ‘pale nymphs’ – tourists – mask dance is now also performed in certain villages as a one-hour event for a fee.

The modesty of boys and girls

Other traditions, however, are almost unbearable for a European, like circumcising girls, which comes down to genital mutilation. To this day, every Dogon girl is circumcised. ‘Yes, girls even look forward to it; it’s a celebration for them,’ says village guide Amadou Karibé. Visitors find out that the circumcision of young girls is deeply rooted in Dogon mythology and closely related to the story of creation. At least now it is understood why such a tradition cannot be eradicated so easily, although the circumcision of women in Mali has long been officially banned.

The boys are not spared either. A joint initiation ritual for young three age groups is held every three years. In the village of Songo, they gather for several weeks below the overhanging, richly painted rock above the village. The village blacksmith performs pruning – for boys it is just a shortcut, but it is done without anesthesia.

millet is the most important thing

Amadou Karibé explains the complicated ritual: ‘Young people are not allowed to cry or scream during circumcision,’ he says. But there is a little help: during circumcision, the other boys stand nearby and sing loudly. ‘In this way, every sob is muffled.’ After everything heals after two or three weeks, the village celebrates a big festival.

The climax is the race between newly crowned men. They run from a large mango tree at the edge of the village to the cliff and draw a circle with their hands. The winner of the first place receives a full supply of millet from the rural community. The runner-up gets the most beautiful girl in the village, and the third-placed gets a cow. ‘In Europe, the order could be different. But here is the most important thing,’ says Amadou.

Cover photo: personnel, Public Domain, Via Wikimedia Commons