Navigating the bail system can be confusing. You might wonder, “If I pay bail, will I ever see that money again?” In most U.S. courts, bail is essentially a refundable deposit that guarantees a defendant will return for all court dates. If the person appears as promised, that money comes back to whoever posted it. However, the details depend on how bail is posted.

The image above shows a courtroom gavel, symbolizing the judge’s role in setting bail. At a bail hearing, a judge decides the bail amount for release. If you pay this amount in cash to the court, the funds are held like a security deposit while the case proceeds. Provided the defendant meets all obligations (attends every court date and follows conditions), the court will refund that deposit at the end of the case, no matter if you are found guilty, not guilty, or the charges are dropped. In short, the outcome of the case doesn’t affect the refund – your compliance does.

For example, imagine paying a $5,000 cash bail at the courthouse. If the defendant appears at all hearings, the court will return that $5,000 to you (minus any court fines or fees owed). The photo above illustrates handing over cash bail. It’s like leaving a refundable deposit: as long as you keep your promise to the court, you get almost all your money back. (Courts typically deduct only any outstanding fines or restitution first. For instance, if you owed $200 in fees on a $5,000 bail, you’d get back $4,800.)

Different Bail Release Options:

- Cash Bail (Refundable) – You pay the full bail amount directly to the court. If the defendant follows all court rules, you get it back after the case.

- Bail Bond (Surety) – You pay a bail bondsman a non-refundable fee (usually 10–15% of bail) to post the full bail amount for you. You don’t get this fee back, because it’s payment for the bondsman’s service (like an insurance premium). Any bail deposit held by the bondsman (as collateral) may be returned after the case if all conditions are met.

- Property Bond – Instead of cash, you use real estate or other valuable property as collateral. The court places a lien on the property, and when the case is resolved, the lien is released (no cash is returned, just removal of the lien).

- Release on Own Recognizance (ROR) – The defendant is released on their promise to return, with no cash paid at all. Since nothing was paid, there’s no refund to be had.

Getting Your Bail Money Back

If you posted cash bail, getting your money back is mostly a matter of procedure. Once the case ends (by verdict, dismissal, or plea), the court issues an “exoneration of bail,” meaning it releases the hold on your funds. You (the payer) will then receive the money back, usually by check or direct deposit. To ensure a smooth refund:

- Attend Every Hearing. The most important condition is that the defendant appears in court as promised. If they miss a hearing or break bail terms, the court can forfeit the bail. That means the money stays with the court and is not returned.

- Follow Court Conditions. Other release conditions (e.g. not committing new offenses) must be met. Any violation can trigger forfeiture of bail.

- Pay Any Court-Ordered Costs. If the court owes you money (your bail deposit) but the defendant was found guilty, the court may deduct fines, fees, or restitution before refunding the balance. So you’ll get back “bail minus any obligations.”

- Submit the Refund Paperwork. Contact the court clerk where you posted bail. You’ll usually need your bail receipt and an ID to request the refund. Each jurisdiction has its own process, so ask the clerk what forms are required.

Bullet List: Key Steps to Recover Your Bail:

- Make sure the case has officially concluded (verdict, plea, or dismissal). The court won’t refund bail until then.

- Obtain an official exoneration of bail from the court (this releases the hold on your money).

- File any required refund request forms with the court clerk, including proof of payment (bail slip) and identification.

- Wait for the court to process the refund. (For example, some courts refund cash bail about 3–4 weeks after case closure.)

- Receive the refund (minus any deductions). The payment usually goes to whoever originally paid the bail.

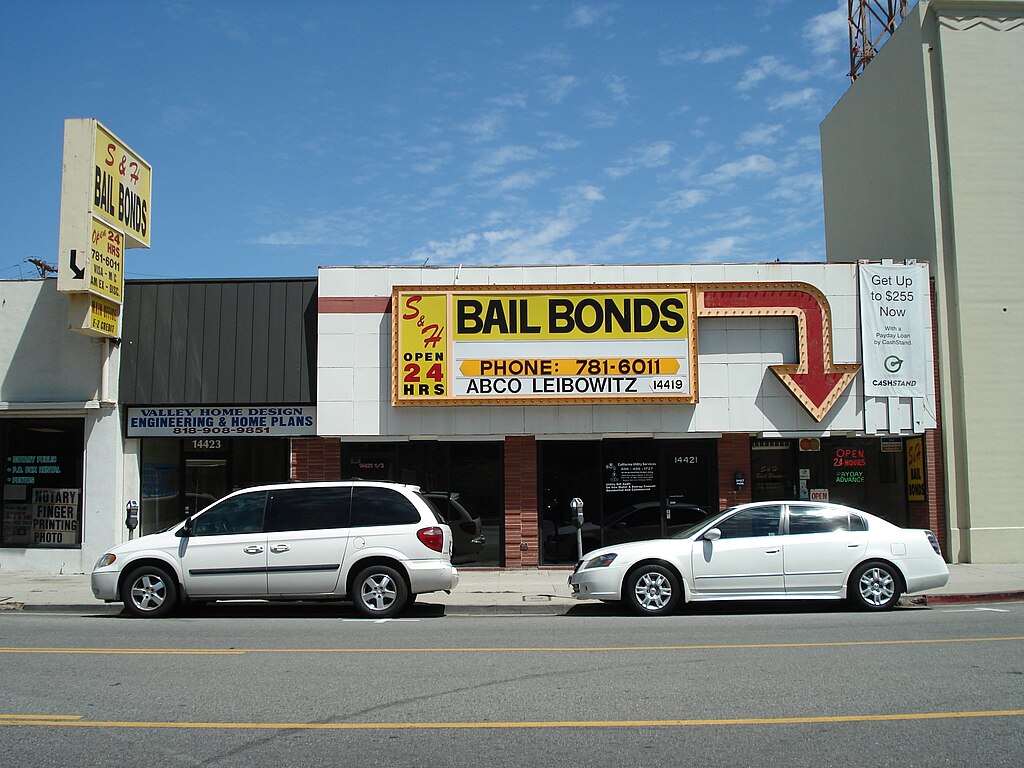

Bail Bonds: Why the Money Isn’t Returned

Many people hire a bail bondsman when they can’t afford full cash bail. In that case, you do not get your bail “money” back in the same way. Here’s why: when you use a bail bond service, you pay the agent a service fee instead of the full bail amount. This fee (often 10% of bail) is the bondsman’s profit for posting the entire bail to the court. That fee is non-refundable – it’s paid upfront for the service, whether or not you show up to court.

In practical terms: imagine a bail is set at $10,000. A typical bondsman charges about 10–15% of that (say $1,000–$1,500). You pay the fee, and the bondsman posts the full $10,000 to free the defendant. If the defendant then attends every court date, the court returns the $10,000 to the bondsman (not to you). The bondsman doesn’t give the $10,000 back to the defendant or family. Instead, the bondsman keeps the $10,000 bond return and only returns any collateral you might have put up. So your net loss is the fee you paid.

Bail Bondsman Fees: The main revenue for bail bonds agents comes from that upfront fee (premium). For most cases it’s around 10% of the bail amount (state law often caps it there; e.g. California is 10%, Colorado 15%). That premium is never returned to you, because it’s their payment for guaranteeing the bond.

Additional Costs: Depending on the state and situation, bail agents may charge extra fees for special services (immigration bonds, paperwork, etc.). They might also require collateral – valuable assets (like a car or house title) – as security. If you attend all court dates, any collateral you pledged will be released back to you. But if you skip bail, the bondsman can seize that collateral to cover losses.

How Bail Bondsmen Make Money

The bail bonds industry is a big business in the U.S. (about $2 billion in annual revenue from roughly 25,000 small firms nationwide). Its profits hinge on the structure above. In summary:

- Premium Fees: As noted, bondsmen charge a non-refundable fee (around 10%) for each bond. For example, on a $50,000 bail, the fee is $5,000. Collecting these fees (from many clients) is their primary income.

- Collateral: Bondsmen often require collateral from clients. This safeguards them: if a defendant absconds, the bail is forfeited and the bondsman can sell the collateral to recoup losses. Collateral effectively ensures the bondsman doesn’t lose money on any individual case.

- Ancillary Services: Some states let bondsmen add fees for extras (processing fees, posting immigration bonds, etc.). These provide a small additional revenue stream.

- Bounty Hunters: If a defendant misses a court date, the bondsman is on the hook for the full bail amount. To avoid that loss, bondsmen often work with bounty hunters to track down and return fugitives. Recovering the defendant can prevent the bondsman from having to pay the court, so it indirectly protects their profits. (Of course, hiring a bounty hunter is a cost, so it’s only worth it if the potential loss is high.)

In effect, a bail bondsman’s income equals the sum of those fees (minus costs). They operate like insurers: charging premiums for risk they guarantee. Because the premium is fixed, they earn money as soon as they post the bond (regardless of case outcome). Their risk is that the defendant might skip court, forcing them to pay the full bail. In practice, thorough underwriting (checking the defendant’s reliability) and collateral help manage that risk.

Example: If a bondsman handles 10 cases with $50,000 bail each (and charges 10% on each), that’s $5,000 × 10 = $50,000 in fees collected upfront. Even if one defendant jumps bail (costing the bondsman $50,000), the remaining fees from the other clients cover it. Over time, the model is profitable.

Key Takeaways

- Cash vs. Bonds: If you post cash bail directly with the court, you will get that money back after the case as long as all court conditions are satisfied. If you’re found guilty, expect deductions only for any fines or fees. If charges are dropped or you’re acquitted, you still get your deposit back – the key is compliance, not innocence.

- Bail Bonds Fees: If you go through a bail bondsman, remember you’re buying a service. The percentage fee you pay (typically 10-15%) is not returned, even if the defendant appears at every hearing. You do not get the bail money back; the bondsman, in effect, keeps it. Any collateral you provided will be returned if the case closes without issue.

- Avoid Forfeiture: Always keep track of court dates. Missing a hearing can forfeit the bail (cash or bond), and that money is lost.

- Consult Local Rules: Bail laws vary by state. Fee caps, refund procedures, and processing times can differ. For example, some counties refund bail around 3–4 weeks after closing the case, while others might take longer. Always ask the court clerk or a legal expert for the specific process in your jurisdiction.

- Know Your Options: If you have no cash, a bail bondsman can secure release, but at a cost. In rare cases, judges may allow release on personal recognizance (no money) or property bonds, which work differently. Understanding these options can save money.

Being informed helps protect your money. If you ever face the bail process, clarify upfront what kind of bail you’re posting and read any bail bond contract carefully. You’ll know: cash bail pays off at the end, but bail bond fees do not. For personal guidance, consider talking to a lawyer or experienced bail agent about your situation.

Sources: U.S. bail law experts and bail bond industry resources.